No One Tool Fits All

When all you have is a hammer

When All You Have Is a Hammer: Recognizing Maslow’s Hammer in Corporate Training

Ever had one of those moments where you look at a problem and, without thinking, reach for the same old solution—because it’s what you know best? I have. And I’ll bet you have, too. There’s actually a name for this tendency: Maslow’s Hammer. It’s a classic mental shortcut, and it’s more common (and more dangerous) in the corporate world than we’d like to admit.

What Is Maslow’s Hammer, Anyway?

Back in 1966, Abraham Maslow famously said, “If the only tool you have is a hammer, it is tempting to treat everything as if it were a nail.” The idea is simple: we get comfortable with certain tools or methods, and before long, we start seeing every challenge as an opportunity to use them, even when they’re not the right fit. Turns out, this isn’t just a Maslow thing; Abraham Kaplan wrote about it in 1964, and similar observations go back even further.

But Maslow’s Hammer isn’t just a catchy phrase. It’s a cognitive bias, a built-in flaw in our thinking. We gravitate toward what’s familiar. We like shortcuts. Our brains are wired to make quick decisions, and sometimes that means we miss better solutions hiding in plain sight.

How This Shows Up at Work

Let’s be honest: corporate life is full of hammers. I’ve seen it play out in training rooms, boardrooms, and strategy sessions. Here are a few ways Maslow’s Hammer sneaks in:

Familiarity and Habit: We stick to what we know, even if it’s outdated.

Cognitive Efficiency: The brain loves shortcuts, so we default to old solutions.

Survival Instincts: We avoid risk, so we oversimplify and stick to safe bets.

The result? We end up applying the same training interventions or decision-making frameworks to every problem. Sometimes, companies treat “more training” as the answer to every workplace issue. If someone’s struggling, send them to another workshop. If there’s conflict, schedule a seminar. It’s the corporate equivalent of hammering away at everything in sight.

The Real Cost of Tunnel Vision

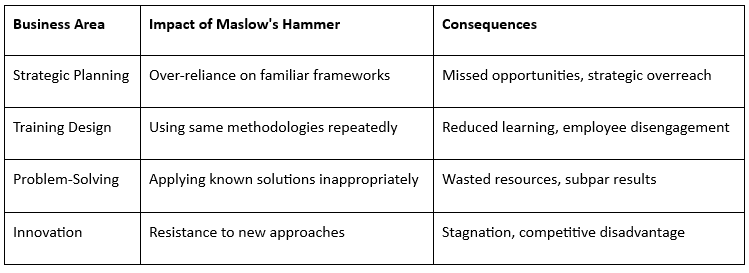

This bias isn’t just a quirky habit—it can have real consequences:

Bias and its consequences in business

I’ve watched organizations double down on the same approach, hoping for different results. History is littered with organizations that used this kind of thinking—relying on what worked before, ignoring warning signs, and tuning out dissenting voices. Disastrous results followed.

Breaking the Habit: What Actually Works

So, how do we break free from the hammer trap? It starts with awareness, but it doesn’t end there. Here’s what I’ve seen make a difference:

Diversify Your Toolkit: Bring in new perspectives. Mix traditional and digital learning. Cross-pollinate ideas from different departments.

Foster Critical Thinking: Encourage people to question assumptions. Make it safe to challenge the status quo.

Structured Decision-Making: Use audits and feedback loops. Involve diverse voices in the design and evaluation of training.

Microsoft, for example, uses scenario-based learning and reflection exercises to help employees spot their own biases. Suncor encourages employees to reflect on instances where they have acted on bias, promoting self-awareness as part of the company culture.

Shifting Culture for the Long Haul

Real change takes more than a one-off workshop. It’s about modeling leadership by being open, investing in ongoing learning, and rewarding experimentation. Standardize processes where it helps, but leave room for creativity and adaptation.

Track your progress—measure learning outcomes, decision quality, and openness to new ideas. The goal isn’t just to avoid old mistakes, but to build a culture that’s always learning and adapting.

Looking Ahead

As new tools and technologies emerge, there’s a risk of trading one hammer for another. Just because something is shiny and new doesn’t mean it’s always the answer. The real skill is knowing when to use which tool—and being willing to reach for something different when the situation calls for it.

In the end, the organizations that thrive are the ones that keep asking: “Is this really the best approach for this problem?” It’s a simple question, but it can save a lot of nails, and a lot of headaches, down the road.