My Definition of Instructional Design and Technology

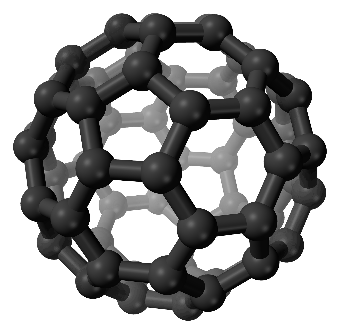

Buckminsterfullerene molecule

I see instructional design as “the deliberate, data-driven, practical, iterative process that recognizes how people learn and puts theory into practice. It promotes human-centered, empathetic, and collaborative experiences that result in qualitative and quantitative solutions to meet specifically stated learning objectives.”

This definition can be visualized as a truncated icosahedron, more commonly referred to as a “buckyball”.

I suggest this image represents the flexibility needed for instructional design to be effective. If one were to imagine that each intersection is a learning goal or objective, there are a multitude of paths that someone can take to get to that intersection. Each of the varied paths to an intersection represents learning theories proven to be effective when solving a learning challenge. From a juxtaposed perspective, the image also evokes a repeatable, recognizable, and stable structure. This represents the same repetitive, iterative process that creates the structure for how instructional designs are built.

To look at the image through another lens, that the entire structure is a learning environment, each intersection can be seen as an individual learner, instructor, or other community member. With this view in mind, one can imagine each learner being a part of a social network and a necessary part of a collaborative whole. Suppose learners are the junctures, and the connections are learning theories and models. In that case, we can imagine any number of combinations of learning theories working together to create a cohesive learning gestalt.

Technology can play a significant role as long as it enhances rather than distracts from the learning process. If a designer merely uses technology for technology’s sake because it is en vogue, it has no business being in the design at all. However, if technology can enhance, improve, or allow for some of the key phrases (mentioned below), technology as a learning tool should be used. Technology should absolutely be leveraged to mine evaluative data when looking for areas in which to improve training performance. These findings provide feedback so that the training can be improved before being utilized again (hence “iterative”).

The key phrases I deem to be absolutely critical for someone else to understand my approach to teaching/training with technology are: data-driven, iterative, and qualitative and quantitative solutions.

By “data-driven,” I mean to convey that the training design is initiated by and created because of a recognized learning problem substantiated by empirical evidence, and that research shows that training is the correct solution to address the root cause of the challenge (rather than some underlying systemic problem).

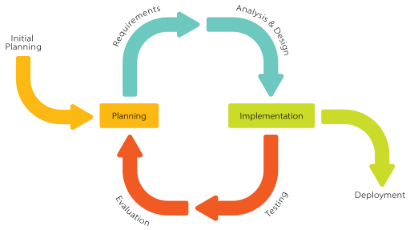

“Iterative” means that an instructional design product is always looking to improve upon itself once feedback on its efficacy is determined. A representation of the process of iteration can be seen in Figure 2.

Iteration process

“Qualitative and quantitative” means that the designs are examined through a multitude of feedback mechanisms so that there are opportunities for iterative improvement. Qualitative feedback can be gathered through student surveys, focus groups, classroom observations, or similar methods. Quantitative feedback also provides crucial data when looking to improve a course or determine its efficacy. This information can be gathered via pre- and post-class knowledge checks, business metrics deltas, or other key performance indicators (e.g., “x” of manufacturing defects per “y”).

The International Board of Standards for Training, Performance, and Instruction’s “Instructional Design Competencies” influenced my definition by stressing the core skills needed to be a designer or design manager. The skills breakdown helped provide a structure for my definition, as well as reinforcing the understanding of the need always to put theory into practice.

Ellen Wagner’s essay most affected my definition of instructional design. Her observations on the difficulty of defining “instructional design” amidst the ever-changing backdrop of the learning and development sphere brought to bear the innumerable skills one must possess to be called an instructional designer. These skills run the gamut from being an audio/video producer to serving as an academic learning theory subject matter expert. Her perspective made me genuinely reconsider my choice in remaining in the graduate program or instead paying to bring my software skills up to snuff. Thankfully, she emphasizes the importance of a background in the academic side of design, highlighting how it contributes to the synergy that fosters effective instructional design.

The explanation of Differentiated Instruction and Universal Design for Learning in Design for Learning also significantly impacted my definition of instructional design. I finally had theoretical names for what I had known all along. His emphasis on the need to be cognizant of diverse, self-motivated, goal-oriented, and active participants in their learning journey shaped my definition by focusing on the uniqueness of each learner.

References:

IBSTPI. (2012). Instructional Design Competencies. https://ibstpi.org. https://ibstpi.org/product/instructional-design-competencies/.

Wagner, E. (2011). In Search of the Secret Handshakes of ID. The Journal of Applied Instructional Design, 1(1), 33-37. https://docs.wixstatic.com/ugd/c9b0ce_4c5d961291de41e58e08576d3c9ee868.pdf

McDonald, J.K., & West, R.E. (2021). Design for Learning: Principles, Processes, and Praxis. EdTechBooks.org. DOI 10.59668/id